Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe's 'biggest regeneration project' fell flat - Nine Elms in London

02-02-2021

Penthouses and poor doors: how Europe's 'biggest regeneration project' fell flat

Few places have seen such turbocharged luxury development as Nine Elms on the London riverside. So why are prices tumbling, investors melting away and promises turning to dust?

Every morning, when Nadeem Iqbal wakes up and walks into his living room, he has a view of a miraculous world first. A crisp oblong of crystal clear water now hangs in the air between two apartment buildings opposite his balcony, a liquid blue block suspended against the sky with the gravity-defying quality of a Magritte painting.

This is the Sky Pool, the latest addition to the luxury residential enclave of Embassy Gardens in Nine Elms, south-west London – one absurdist step beyond the private cinema, indoor pool, gym and rooftop lounge bar. It was dismissed as a “crackers” PR stunt when the plan was unveiled by Irish developer Ballymore in 2015, a fantastical aquarium of captive high net worth individuals for the rest of us to gawp at from far below. Surely it would never materialise. But last week the scaffolding was taken down to reveal a bright blue rectangle hovering against the leaden January skies, 10 storeys up in the air – just outside the 30-metre bomb blast seclusion zone around the new neighbouring US embassy.

It has been billed as the world’s first swimming-pool bridge, a dazzling feat of acrylic engineering that will span the 14-metre gap between the two buildings and give residents the feeling of “floating through the air in central London”. But, although he lives in Embassy Gardens, Iqbal and his neighbours will never enjoy the thrill of going for an aerial dip. “We have a front-row seat of the Sky Pool,” he told me. “But the sad thing for us, living in the shared-ownership building, is that we will never have access to it. It’s only there for us to look at, just like the nice lobby, and all of the other facilities for the residents of the private blocks. Nobody expects these amenities for free, but we’re not even given the choice to pay for them.”

For Iqbal to reach his two-bed flat – valued at £800,000, of which he owns a quarter and pays rent on the rest – he must walk past the grand, hotel-style main entrance to the complex, flanked by supercars with personalised number plates, to the back of the development, past construction fences and piles of rubble, to a small door located between ventilation grilles and a bin store, facing on to a railway line. “There’s a reason they’re called ‘poor doors’,” he said. “I grew up in South Africa, in a country that was racially segregated, but in London there is still really bad class segregation. We have a mortgage and we pay our rent, but every day we are made to feel inferior, like the have-nots of Nine Elms.”

Stretching across a 230-hectare riverside swath from Vauxhall Cross to Battersea Power Station, straddling the boroughs of Lambeth and Wandsworth, the Vauxhall Nine Elms Battersea (VNEB) “opportunity area” has been trumpeted as the biggest regeneration project in Europe. When Boris Johnson, as mayor of London, launched the plans in 2012, he described it as “the greatest transformational story in the world’s greatest city”, the “final piece in the jigsaw” of central London. Once a place of low-slung warehouses and logistics depots, it is now a very visible presence on the London skyline. Competing stacks of luxury flats have sprouted along the river, replacing the elm trees that once stood here with a forest of concrete and cladding, a garish collage of mirrored glass, coloured plastic panels and fake bricks.

With around 5,000 homes completed over the past five years, and a further 15,000 in the pipeline, it is now possible to get a sense of what kind of place is being created here, what effect the planning policies of the past decade will have in reality. The results so far are not encouraging. Roughly the size of Monaco, the new district has all the makings of a similarly exclusive fiefdom, an international investors’ playground where regular Londoners are pushed to the very edges, or cut out of the picture altogether.

The capital is well used to high-rise, high-end totems by now, but VNEB takes the iniquities of the real estate-industrial complex to extremes. It is a place where penthouses with private chapels and running tracks loom above crumbling council estates across the railway line, where scores of flats lie empty, held by secretive shell companies in off-shore tax havens, and where the division between absentee investors and owner-occupiers confined to poor doors could not be more stark. Dogged by allegations of cronyism and gerrymandering, it is the product of politicians in thrall to property developers, driven by a blind faith in the market – even when investors started to realise that they might have bought into a mirage.

AAll along the railway line, running south-west from Vauxhall to Battersea, stand dense rows of apartment blocks similar to Iqbal’s – the “affordable” components of the luxury developments, shuffled to the back of the plots where land values are lowest, hidden from view along with the garages and service entrances. It is the same story across the road, where the angular blocks of the Riverlight development march along the Thames, along with a shared-ownership building that, for the last few years, has faced on to the noise and dust of the construction site for London’s new “super-sewer”. Brightly coloured vents and glass elevators reveal that this comes from the stable of architects Rogers Stirk Harbour, but the stylistic add-ons do little to disguise the reality of serried slabs of investment units garnished with fenced-off slivers of lawn – to which the affordable housing residents’ key fobs do not grant them access.

Next to Embassy Gardens stands The Residence, by Bellway Homes, offering “elegant Manhattan-style living” in a series of brick towers jazzed up with gaudy red and yellow panels. A broad staircase leads up from the street to a podium garden, but a tall fence with an electric gate stops the second-class residents from getting in. “We are strategically excluded from being part of the community,” said Jason Owusu-Frimpong, who lives in part of The Residence facing the railway line, managed by housing association L&Q. “We would happily pay for gym membership, if we were allowed to, but the management says it’s not for us. Meanwhile, the car park they told us was only for disabled use is now being sold off to wealthy international residents.”

A few metres from his front door sit a pair of souped-up sports cars with Qatari number plates, parked ostentatiously on the pavement blocking an emergency exit, with a clutch of unpaid parking tickets flapping in the breeze beneath their windscreen wipers. The concierge is exasperated. “They are deliberately doing this,” said the man behind the desk in the private building’s lobby, to which Owusu-Frimpong and his neighbours are denied entry. “We have sent endless letters to the residents in question, but there’s nothing we can do about it. They come here from the Gulf for a few months of the year in holiday mode, race up and down the road, revving their engines late at night, then they ship their cars back home and never pay the fines.”

VNEB is emerging as a place of two communities, with a bitter sense of division nurtured by the very fabric of the neighbourhood. The exclusion has been designed into the buildings, streets and public spaces, and is enforced by the private management regimes that govern them. If it is an opportunity area, it has been an opportunity for trialling a new form of social apartheid on an industrial scale.

Andrea Franzel lives in an apartment in the Chancery building of Embassy Gardens, a shared ownership block managed by the Peabody housing association. After months of navigating dense bureaucracy, as chair of the residents’ association, he secured some funding to buy a painting for the building’s bleak communal lobby, along with a mirror and a small console table. But, after three years, Peabody’s neighbourhood manager ruled that the table was a fire hazard, and had it removed. “It sounds like a small thing,” said Franzel, “but that little table was part of our community. We used to buy fresh flowers and leave things for each other. Now we have nothing.” Next door, the lobby for the private residents looks like a club-class lounge, teeming with expensive hazards, from the thick-pile carpets to marble coffee tables and inviting sofas. While these residents get packages delivered to their door, Franzel and his neighbours find their parcels often go missing, dumped in a pile downstairs. Since the pandemic struck, only the lift lobbies of the private blocks have been supplied with pumps of hand sanitiser.

Residents on both sides have reported a host of issues with the buildings’ construction quality, from broken windows and doors to sinks that weren’t connected to waste pipes when they moved in, leading to serious internal leaks – an ongoing catalogue of calamities reported by a pair of Instagram accounts, @real_embassygardens and @ballymorehell. Private leaseholders are just as furious, leaving online reviews raging about everything from poor workmanship to extortionate service charges and “monopolistic” energy contracts.

A spokesperson for Ballymore says: “We aim to create great places and positive experiences for everyone who lives on our sites. All residents at Embassy Gardens receive the same service in terms of estate management, security, fire command and control, general building safety and energy supply.” They stress that the affordable housing blocks are managed by Peabody and Optivo, which “had the option to choose which facilities they wanted to buy into for their residents”. As for the construction issues, they say: “We take any issues seriously and have two full-time aftercare managers on site, as well as a construction team completing the final residential building, so any issues can be dealt with swiftly.”

Spokespeople for Peabody, Optivo and L&Q all say that it is never their intention to make any community feel excluded, and that their policies do not include access to the private amenities in order to keep the service charges to a minimum. They insist that these terms were made clear to residents at the point of sale. As for being given the option to pay for additional services, such as gym membership, L&Q adds that “following feedback from residents, we are reviewing this approach”.

For Ravi Govindia, the Conservative leader of Wandsworth council since 2010, and key proponent of the area’s regeneration, it is a question of choice in a free market. “One shouldn’t create a deliberate division without telling people what their money buys,” he said. “If people were led to believe they had access to everything, then in the small print it said otherwise, that would be wrong. But it’s up to people to make their choices.”

When it comes to the criticism that the area is a ghost town, full of empty flats for foreign investors, not real homes that London needs, Govindia shrugs it off. “London is an international city,” he said. “It has always had people who don’t live in their home for 365 days a year. And the reality of overseas investment from off-plan sales has, in many cases, delivered these developments.”

The district’s supposed popularity with foreign buyers has long been held up as a sign of success, with models of the VNEB developments a regular feature at the Mipim property trade fair in Cannes for the past decade. The primary purpose of the flats as safe deposit boxes, not homes, is evident when you look at the floor plans: this is “investment grade space”, with tiny rooms that just meet the minimum regulatory allowances, and emphasis placed on transport links and proximity to Westminster. So how attractive has this promised land actually proved to be for foreign buyers?

Not very, the data suggests – despite everything that estate agents were doing to prove otherwise. In 2016, shortly after many of the projects launched off-plan sales, property analytics firm Propcision observed a strange phenomenon. Hundreds of luxury flats in Battersea and Nine Elms were continually being listed for sale on sites such as Rightmove and Zoopla, then taken down and immediately relisted. It was being done at such frequency across so many developments that it distorted the market across the whole area. “It gave the impression that there was not only a lot of activity,” said Propcision’s director, Michelle Ricci-Zak, “but that the average price in that area was going up – when actually we proved it was going down.”

In one snapshot, looking at an agency that listed 35 new-build properties for sale during an eight-month period, the constant relisting made it look as if there were in fact 368 properties for sale. Rather than roughly £50m in market value of apartments advertised, the distortion would have made it appear as more than £500m. In another example, a £3.6m flat was re-listed 15 times in six months, making it seem like the average asking price in the area was skyrocketing. The manufactured flurry also gave the impression to potential buyers that flats were “flying off the shelves”, she said, when in fact the developers were struggling to offload them. The reality was that they were selling off homes in bulk at steep discounts to corporate landlords and institutional investors, with prices slashed by up to 38%.

As off-plan customers began to suspect that they had bought into an illusion, they rushed to sell their speculative investments back to the developers, leading to a phenomenon known as “Nine Elms disease”, as up to £2m was knocked off the price of some penthouse flats. “Battersea panic stations” announced one headline. While the practice of immediate relisting has now been banned, and prices have mostly stabilised, there are still signs of a glut of too many similar high-end flats, with some investors trying to dispose of entire floors of towers in Vauxhall. “It seems some people took a big bite of the pie,” said Ricci-Zak, “and it didn’t taste so good.”

IIt was the 180-metre-tall St George Wharf Tower, by the Berkeley Group, which began the craze for what has become a crowd of swollen shafts at this bend in the river. The tower was initially refused permission by Lambeth council, but in 2005 then-secretary of state John Prescott gave it the rubber stamp, despite warnings from his expert advisers that it “could set a precedent for the indiscriminate scattering of very tall buildings across London”. And so it did.

As you exit Vauxhall station, the first of the priapic bunch to smack you in the face is the Damac Tower, formerly known as Aykon, designed by KPF architects and developed by Damac Properties – the same firm behind Donald Trump’s golf course resort in Dubai. It was billed as the very pinnacle of luxury living, “a global symbol of opulence” with a full-length pool on the 23rd floor and all interiors designed by Versace, offering buyers the chance to “live the complete Versace lifestyle, a fantasy turned into reality”. It now stands as a menacing Goliath on the edge of the Vauxhall gyratory, its lumpen blocks smothered with different cladding panels, as if several unrelated buildings have been chopped up and bolted back together without the instructions.

Sales launched in 2015, with flats pitched at Mayfair prices, reaching more than £2,000 per square foot – twice as much as neighbouring towers. But the Versace label hasn’t proved as much of a lure to foreign buyers as hoped. Over the past five years, prices for flats in “the ultimate in branded living experience” have dropped by an average of 20%. “The closer it gets to the completion date of these towers,” said Ricci-Zak, “the more desperate it seems the contract holders are to get out.”

Reaching 170 metres in height, the Damac Tower is part of the so-called “Vauxhall cluster”, a row of towers that now forms a motley wall on the skyline. Separated by roaring six-lane roads, the buildings are actually spaced too far apart to form any kind of cluster, standing with the awkward air of a socially distanced gathering of portly executives in ill-fitting suits.

The cumulative effect of such a bloated outcrop was never properly considered. The 2012 planning framework for the area, drawn up by the Greater London Authority with input from Lambeth and Wandsworth, set a maximum height limit of 150 metres, with the taller St George Tower as “the pinnacle of the cluster”. But the plan was soon breached with the arrival of One Nine Elms, an apartment and hotel complex rising up to 200 metres, also designed by KPF. In a promotional video the architects argued that their site was at the geographic centre of the future crop, so it should therefore be the tallest, with lesser towers stepping up to it “in a sort of swirl”. The planners were convinced. “The man in the street might not understand how it works,” said Govindia, “but it is a well-tested principle that you organise tall buildings in a tight cluster, ascending to a peak.” KPF declined to comment, and their video has now been taken down.

What this picturesque notion failed to foresee is that, once one 200-metre tower had been given permission, it would encourage others to follow, with the threat of expensive legal action if refused. It was a repeat of Prescott’s St George Tower fiasco, setting a precedent for neighbouring landowners to inflate their plans.

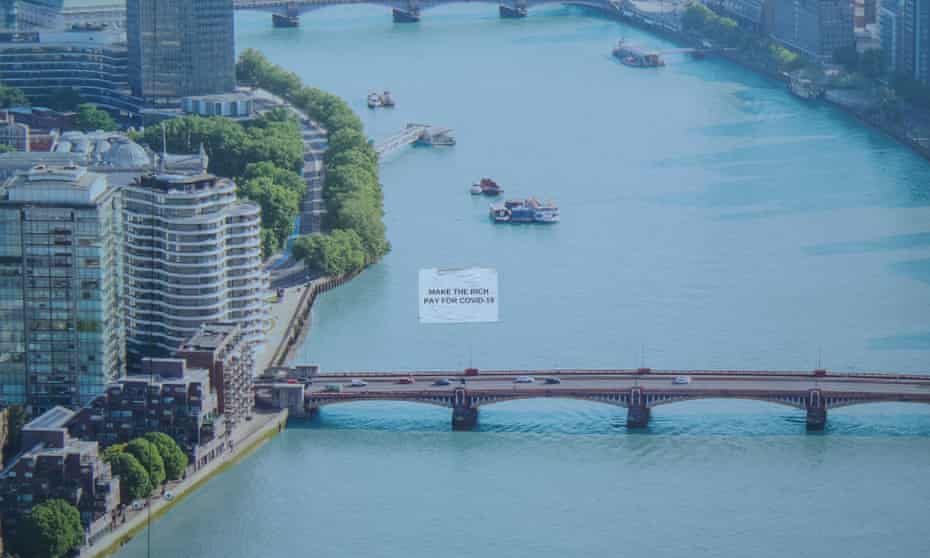

A proposal for a pair of towers by Zaha Hadid Architects on the site of Vauxhall bus station, backed by one of Saudi Arabia’s wealthiest families through a Guernsey-listed company, was cranked up several stories to 185 metres, and given permission by secretary of state Robert Jenrick last year. A gargantuan trio of ziggurat-shaped towers reaching 200 metres is now well underway nearby, set to be the crowning feature of One Thames City, a complex of 12 blocks by Chinese developer R&F Group on the site of the former New Covent Garden flower market (since relocated to a temporary shed down the road while a permanent home is developed). Designed by US firm SOM, it has been pitched as “a new benchmark in enduring luxury”, complete with a 30-metre pool and cigar bar, as well as a landscaped Chinese garden, described as “undoubtedly one of the most fascinating sceneries the Thames will behold”. The construction hoarding shows how the penthouse terraces will even come with their own private infinity pools looking out over the river – a vision recently adorned with a protest sticker with the words: “MAKE THE RICH PAY FOR COVID-19”.

Not all Chinese buyers are impressed. “If you buy prime property in London,” said Ling Zhang, a Chinese investor who has acquired a handful of new-build apartments in the capital in recent years, “you want it to feel like London – not China. I also think there are far too many identical ‘luxury’ apartments being built in the same location for it to be a good investment. Chinese buyers are very concerned about location, and we mostly prefer north of the river, close to the universities. Many people send their children to London to study, then rent out the apartments when they graduate.” Henry Pryor, a prime property buying agent, is frank: “I’d rather buy a flat in Wuhan than Nine Elms today.”

It appears that the world of international diplomacy might feel the same way. The US embassy was supposed to be the first of many missions to migrate across the river, and Nine Elms is still being promoted as “London’s new diplomatic quarter”. China was set to move its embassy here, as was the Netherlands, but both have backed out. The Dutch sold their plot to a hotel developer in 2019, while the Chinese have chosen the decorous surrounds of the old Royal Mint next to the Tower of London. Perhaps they shared Donald Trump’s assessment of Nine Elms, when he refused to cut the ribbon on the new embassy: a “lousy location”.

The turbo-charged speculative development along the river has its origins in an unlikely place. It was the socialist mayor of London Ken Livingstone who first designated this part of the capital as one of his 28 “opportunity areas” in the 2004 London Plan, along with places such as King’s Cross, Elephant and Castle, the Greenwich peninsula and Paddington. The strategy was for a Robin Hood model of regeneration: a tidal wave of foreign investment would be actively encouraged, and tall buildings welcomed, in the belief that a large bounty could be creamed off for the public good. The target was for half of the housing to be affordable. If developers couldn’t meet this target, they would have to produce a financial viability assessment to prove why it wasn’t possible.

But it didn’t quite go according to plan. Rather than being an exception, viability became used as a regular get-out clause. Each time, it was a similar story: having paid so much for the land, and expecting costly construction fees, while forecasting low sales prices, the developers could make it look like they simply wouldn’t have any money left to pay for affordable housing. Meanwhile, the viability assessment allowed their 20% profit margin to be safely preserved.

In 2012, just as the plan for the VNEB area was being drawn up in City Hall, the Conservative-led coalition government accelerated this trend by placing viability at the very core of national planning policy: the ability of the developer to make a profit would trump everything else. They then watered down the definition of “affordable” housing to mean up to 80% of market rate – hardly affordable for many in London. With David Cameron in No 10, Boris Johnson in City Hall, Wandsworth council’s former leader Edward Lister as Johnson’s deputy mayor for planning, and Ravi Govindia at Wandsworth town hall, the VNEB opportunity area became the ultimate testing ground for this mighty engine of deregulation, a developer free-for-all where anything would go.

Smoothing the path was Peter Bingle, a former flatmate of Govindia, and a Wandsworth councillor turned housebuilder lobbyist. His company, Terrapin Communications, has worked on behalf of a number of landowners and developers in the area, including Ballymore and Bellway, to help assist the passage of planning applications for hundreds of luxury homes. In 2018, a freedom of information request uncovered a cache of emails showing Bingle asking Govindia to intervene in decisions and circumvent council officials he believed were being obstructive to his clients. (There is no suggestion of wrongdoing.) In 1987, when he was chairman of the council’s property sales committee, Bingle stated: “My aim is to reduce the number of Council properties in Wandsworth from 35,000 to 20,000, and to make Battersea a Conservative constituency.” In critics’ eyes, similar ambitions are driving the development of Nine Elms, which will see a new ward boundary drawn around the luxury enclave.

“Tory-led Wandsworth has always pioneered the neoliberal policies that created the housing crisis,” said Aydin Dikerdem, a Labour councillor for the Queenstown ward, in which much of the development is underway. “They launched the right to buy before it was national policy, and accomplished the mass privatisation and demolition of entire estates, as well as the outsourcing of services. What’s going on in Nine Elms and Battersea has nothing to do with maximising social good or creating mixed communities. It is pure social cleansing.”

Govindia insists that Wandsworth “hasn’t stopped building housing, it’s just not as plentiful as it has been in the past”. He said that the council has embarked on a programme to build 1,000 homes “in the nooks and crannies” of existing council estates, with 60% at social rent levels. (The Labour leader of Lambeth, Jack Hopkins, declined to be interviewed for this article.)

DHikerdem identifies one particular element as the “cardinal sin” of the whole regeneration project. As part of the plan, the Northern line is being extended south-westwards, with two new tube stations, one at Nine Elms and one at Battersea Power Station, part-funded by the developers to the tune of £266.4m – money, he argues, that would otherwise have been spent on affordable housing. The 2012 planning framework states that, while both Lambeth and Wandsworth would usually demand between 33-40% affordable housing, contributions towards transport infrastructure should be prioritised here instead. Given the need to pay for the tube stations, it concludes, a target of just 15% affordable housing should be allowed. “It is pure taxpayer subsidy to improve house prices in a luxury development,” said Dikerdem.

While the affordable housing quota averages around 18% across the VNEB area – including council-owned sites – and more like 21% in the part that sits within Labour-led Lambeth, it has been reduced even further in the case of the Battersea Power Station development. Having originally agreed to make 15% of the 4,239 planned homes affordable, the Malaysian-owned development company convinced the council to slash the number by 250 to just 9% in 2017, citing “technical issues” with restoring the historic structure. Here, the separation between the haves and have-nots will be even more acute. While the flats for private sale are housed in overwrought buildings by Norman Foster and Frank Gehry, which do their best to block views of the power station from all directions, the “affordable” homes are being built half a kilometre away, across the busy main road, and butted up against the railway tracks. Residents will have little chance of feeling part of what the developers describe as “one of the most exciting and innovative mixed-use neighbourhoods in the world”.

The depressing reality of what has happened here becomes all the more stark when you look across the river. Right opposite the power station stands Churchill Gardens, a vast postwar housing estate designed by distinguished architects Powell and Moya, built to house 5,000 people across a 12-hectare site, with several blocks now listed and around half still council-owned. Developed by the London County Council, it was designed to accommodate a balanced cross-section of society, with the highest standards of housing for all – and not a segregated entrance in sight.

“There was once a world where you could build riverside council homes,” said Dikerdem. “We’ve gone backwards since then. That’s why what has happened here is so upsetting. We are never again going to have all this abandoned industrial space on the river, which could have really transformed the lives of people in a borough in which thousands of people are statutorily homeless, and tons of professionals are spending all their income on private rent. It was a historic opportunity, but we’ve ended up with loads more luxury skyscrapers, which is not what the city needed.”

Some names have been changed

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, sign up to the long read weekly email here, and find our podcasts here