A forbidding clock tower rises above the arched windows of a former Victorian workhouse in east London’s Mile End, behind a hoarding which trumpets the conversion of the crusty old pile into an enclave of luxury apartments. The mortuary, morbidly located next to a graveyard at the end of this brutal conveyor-belt complex, has been reborn as The Lodge, a two-bed flat for £999,995 – the kind of inflated price that is increasingly familiar, even here in one of London’s poorest boroughs.

But buried among the workhouse chic and the new brick apartment blocks is an unlikely experiment in building homes that will remain affordable to local people forever. After a decade of campaigning, the East London Community Land Trust has succeeded in creating housing where the prices will be linked to local income in perpetuity, entirely detached from the superheated speculation of the property market.

“It’s incredibly exciting to finally see it for real,” says Taj Uddin, a 40-year-old local government worker, walking into the living room of his new two-bed flat for the first time, where full-height windows lead to a balcony looking out over a communal lawn. Born down the road, Uddin has watched as the neighbourhood’s property prices have spiralled beyond his reach, forcing him to live with his brother. Jessie Brennan, a 34-year-old artist, was in a similarly precarious situation, having rented in the area for years before being priced out to the Thamesmead estate, an hour’s bus and train ride further east, where she has been living as a property guardian.

“As soon as I heard about the community land trust, it was a no-brainer,” she says. A CLT puts the housing in community ownership, with homes sold or rented at a rate linked to local wages and membership open to anyone with a connection to the area. It’s a radical model that effectively takes housing out of the property market and pegs it to the labour market instead. “It’s crazy how in this country we treat housing as an asset for accumulating wealth,” Brennan adds. “I don’t see why you should be able to make a profit from your home.”

She and her partner, together with 23 other households, will move in this month, paying less than half the market rate for their properties. One-bed flats offered by the CLT are around £130,000, while identical private flats in the rest of the development start at £450,000. The catch? When they come to move on, they will have to sell at a price that remains pegged to local earnings, forgoing the potential windfalls of London’s property lottery.

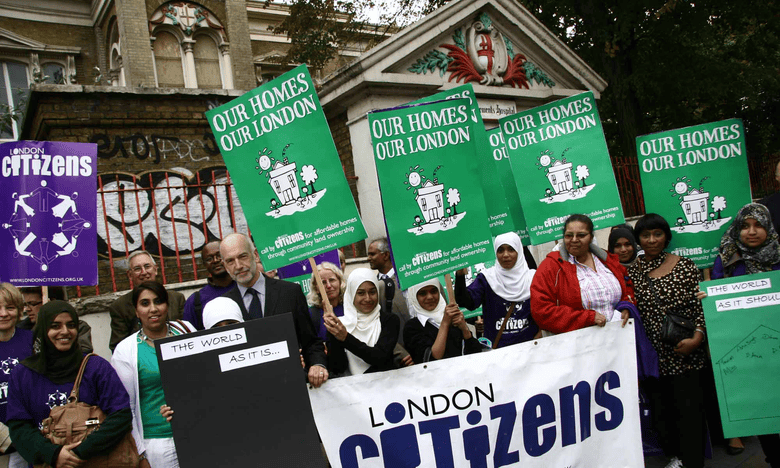

As the capital’s first community land trust, the St Clement’s project was made possible because the site, home to a mental health hospital that closed in 2005, was owned by the Greater London Authority. After a long grassroots campaign, led by charity Citizens UK, the GLA asked the successful developer, Linden Homes, to work with the East London CLT group, which had also bid for the site.

The 23 CLT flats represent a small proportion of the overall development of 252 homes, comprising just under a third of the 35% affordable quota, with the rest rented out by the Peabody housing association. It’s a fraction of what the campaign had originally hoped for, but they have laid the groundwork for a form of truly affordable housing that is gathering momentum across the country.In 2010, there were 36 community land trusts in England and Wales; now there are 225 groups, with 700 homes built to date and a further 3,000 in the pipeline to be completed by 2020. With CLTs taking off in low-income inner-city areas, they can no longer simply be dismissed as the niche preserve of Grand Designs enthusiasts.

“It has become a real resistance movement now,” says Catherine Harrington, director of the National Community Land Trust Network.

“People are demanding more of a say about what regeneration looks like, instead of sitting back and being told what the future of their area is going to be,” she adds. “It’s about changing the narrative of housing: building homes rather than investment units; having security and stability in a particular place, rather than being forced to move every six months; and mobilising popular support for development.”

In December the government announced a new £300m Community Housing Fund, of £60m a year over five years, to support CLTs, which Harrington says could triple the number of homes delivered.

Community ownership of land has a long history in the UK, dating back to the Garden City movement and beyond, but the community land trust model is something of an import. It was developed in the US, born out of the civil rights movement in the southern states in the 1960s, where it enabled African Americans to control the production of their own homes and food. It was revived in the 1980s, and America’s largest CLT, the Champlain Housing Trust in Burlington, Vermont (founded by Bernie Sanders, then mayor of Burlington), now owns more than 2,000 homes.

In England, CLTs began cropping up in the early 2000s, and have mainly operated in middle class rural areas, providing a means of preserving community stability against influxes of second-home buyers. But over the last few years they have begun to be used in urban locations as both a powerful tool in the battle against gentrification and as a means of reviving blighted empty streets.

“They have the potential to be a hugely disruptive force,” says housing and planning expert Stephen Hill, who advises many of the urban CLT groups across the country. “They allow people to say ‘the land market doesn’t work in this area, so we’re going to get together and change it’.”

According to Hill, the crucial moment came in 2008, when the Housing and Regeneration Act gave community land trusts a legal definition for the first time, which he describes as “one of the most important but barely noticed political acts of recent years”. Stating that CLTs must be set up expressly to further the social, economic and environmental interests of their communities, and be democratically accountable to their communities, it aligned them with the objectives of local authorities at every level.

They are also a phenomenon that enjoys cross-party support, attractive to different political administrations for different reasons. For Labour, they represent bottom-up communitarianism; for the Tories, they are self-help and the “big society” in action; for the Lib Dems they embody the great liberal quest for land reform. And, crucially, for all local authorities being forced to sell-off their council housing stock, they are one of the only forms of affordable housing that are immune from the right to buy.

From Leeds and Liverpool to Oxford and Hastings, the nature and purpose of CLTs can be hard to generalise because they are each responding to the specific local housing need in their respective areas. In Anfield, the Homebaked CLT began with the revival of a bakery near the Liverpool FC football ground, and it is now looking at ways of tackling other empty units in the area to provide workspace for social enterprise, affordable housing and “spaces to meet, chat and celebrate”.

Across town, Toxteth’s Granby Four Streets CLT is about bringing back life to rundown rows of tinned-up terraced housing, stabilising the fragmented community and attracting people back to the area. Its architects, Assemble, won the Turner Prize for their work there, and are now working with a CLT group in Hastings to develop community-led housing in the Ore Valley, one of the town’s most deprived neighbourhoods. Conscious of the town’s rising prices, they are trying to establish the project before the gentrification tipping point.

In Camley Street in Camden, a stone’s throw from the high-end towers of the £2bn King’s Cross regeneration project, values have already exploded, and development pressure is threatening to squeeze industrial space out of the area. The neighbourhood forum has come together with local businesses to form a CLT that is proposing a dense mixed-use scheme of hundreds of homes and further employment space, with rental income fed back into the community over the long-term. It’s still in the early stages, but it could provide a template for how to build a truly mixed-use urban quarter, without a developer creaming off the value.

In such highly prized urban areas, access to land is perhaps the biggest obstacle facing CLTs; but that’s why, in the absence of longterm-thinking landowners, local authorities are perfectly placed to help. By law, councils are required to dispose of their land on the basis of the “best consideration” reasonably obtainable, which should take into account long-term value. Social and economic benefits can justify the sale of land below market price – local authorities are not required to automatically flog their land to the highest bidder.

In Lewisham, home to a couple of pioneering self-build council housing projects in the 1980s, the local authority recently ran an open competitive EU bid for a site in Ladywell, weighted in favour of community benefits. It awarded it to the Russ CLT, which plans build 33 permanently affordable homes at a range of tenures, due to start construction next year.

“Local councils are under pressure to sell assets for maximum value to balance the books,” says Russ founder Kareem Dayes, who grew up in one of the self-built homes on Walter’s Way in Honor Oak. “But by working with us, the benefits for the area in the long-term will outweigh any nominal cash raised upfront.”

In Bristol, a city that has long been shaped by strong third sector organisations, the council is taking an active interest in facilitating the work of CLTs, rewriting its policies to take community-led development into account. “The main driver for us is about people being in more control over their own areas,” says the Labour council’s cabinet member for housing, Paul Smith.

“Council housing has historically served a significant need, but what wasn’t thought about so much was how those communities would be sustainable in the long-term,” he adds. “Community-led housing might traditionally be seen as a middle-class, middle-aged solution, but we’re now getting a lot of demand from working class areas for this kind of approach too.”Bristol CLT has completed its first project of 12 homes on the site of a former school, bought from the council for £1, where residents were involved in finishing elements of the interiors, accumulating “sweat equity” in the process. They are now working on a second scheme of 25 homes for another council-owned site. Smith says the ambition is to scale up the projects: by 2020, he wants to see the community sector building 300-500 homes across the city, a level that would outstrip what the council or housing associations have achieved in recent years.

Critics argue that community housing represents no real solution to the housing crisis. Others see it as a symptom of councils shirking their responsibilities, or a result of having their own housebuilding capacities relentlessly slashed. But, as Catherine Harrington points out, one of the biggest obstacles to the government achieving its target of building one million homes by 2020 is nimbyism – a phenomenon that community land trusts are perfectly placed to counter.

“In many cases, CLTs have a unique ability to gather popular support for new development, because the local community is in control,” she says. The proposals are defined and driven by local residents themselves, with the long-term interests of the neighbourhood at the very heart of the plans.

Tony Wood, a founding member of the St Ann’s Redevelopment Trust (or StART) CLT in Haringey, north London, has had years of experience as a community campaigner and never found people so receptive to a cause. “I’ve stood on street corners leafleting passersby about saving parks or opposing planning applications,” he says. “But I’ve never had such a positive response as when trying to get support for the community land trust. Everyone understands the desperate need for affordable housing.” The borough’s council house waiting list is 10,000, and around 90% of those families “will never be housed in social rented accommodation”, according to the council’s website.

Such is the level of support for StART, that the group is forging ahead with plans for up to 800 homes on an NHS-owned site, which has existing planning permission for a private development of just 470 homes – against which there has been substantial local opposition. Only 14% of the homes in the previously proposed scheme would be “affordable” (ie up to 80% of market rate), whereas the majority of StART’s homes would be pegged to between 30-40% of the median local household income.

“People say that if we can guarantee the homes are going to be genuinely affordable and stop local people moving out of the area, then they won’t object,” says Woods. “But it’s better than that. The joy with the rental side is that, once we’ve paid off the mortgage, we would have nearly £6m income a year to use for local community benefit.”

The group ran a successful crowd-funding campaign to cover architects’ fees for a masterplan, and is currently in talks with the NHS and the council. “The planning officers were saying it’s nice for the community and the council to be working on the same side for once,” says Woods. “It doesn’t happen very often with large housing developments.”

It would be the biggest CLT in the country by a long stretch if they managed to pull it off. Together with Camley Street, Russ, St Clements, Brixton Green and an alternative plan for the West Ken and Gibbs Green estate in Earl’s Court, it amounts to 2–3,000 permanently affordable homes in London alone. “If we get more schemes of this scale, mayor Sadiq Khan might actually achieve his 50% affordable target,” says Hill.

During his campaign, Khan talked of wanting to see 1,000 CLT homes built by the end of his first year as mayor – though he has yet to announce any policies that might begin to help. And StART’s efforts may still come to nothing. “A big housebuilder like Barratt Homes could come in and offer to pay way over the odds for the site, so we might all be putting in huge amounts of work for no reason,” Woods adds.

“But we want to try. I cycle past the site every day, and I don’t think I could have lived with myself if I hadn’t tried to do something to stop it from becoming homes that local people couldn’t afford.”

Oliver Wainwright will be chairing a debate on UK housing on 19 January at Central Saint Martins, London, as part of the Fundamentals debate series

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here