That landlords are signed-up members of the ageing population. Twelve years ago, just under a quarter (24 per cent) of buy-to-let landlords were aged 55 or over. In 2016, the proportion had risen to 61 per cent. In 2004, some 41 per cent of landlords (buy-to-let, as well as other types) were aged under 45. Since then their share has dropped to 20 per cent.

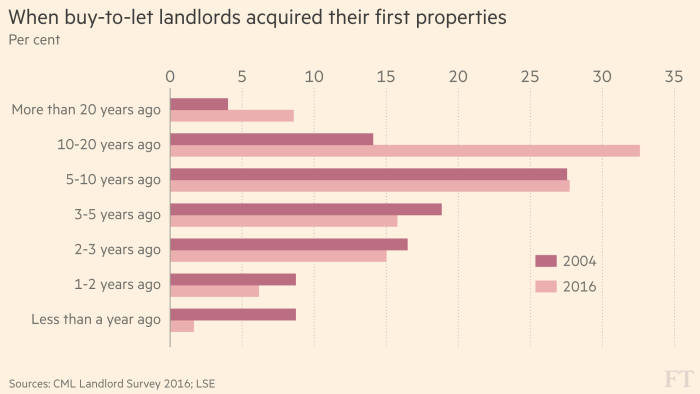

Those who bought 12 years ago appear not to have been replaced by new, older buyers: nearly two-fifths of current buy-to-let landlords purchased their first property at least 10 years ago. Then, most landlords were between 35 and 54; now, most are aged between 47 and 66.

Where is the data from?

The biggest survey yet to be conducted in a relatively poorly-researched area of the housing market, the study by academics at the London School of Economics and Politics updates a similar exercise by LSE in 2004. Then, the postal survey asked a range of question of 1,340 landlords across the UK. The latest survey — conducted online — drew responses from 2,517 landlords. Commissioned by the Council of Mortgage Lenders, the industry body, it was carried out in June.

What’s behind the ageing trend?

As house prices have risen, it has become harder for younger people to get on to the housing ladder: first-time buyers and home movers have got older, and the same forces have affected landlords. “As the age of first-time home buyers rises, so the age of first-time investors would rise as well,” says Kath Scanlon, co-author of the LSE study.

This slowing of the market at the younger end is backed by other data in the survey: in 2004, 18 per cent of buy-to-let landlords had bought their first rental home within the previous two years. The figure is now about 7 per cent.

Many landlords buy a home for themselves to live in, then go on to invest in buy-to-let. Others rent out the property they originally bought for owner-occupation when they move up the housing ladder, previous LSE research suggested.

Ministers and regulators have been bearing down on landlords with new measures on borrowing and tax. Does the survey have anything to say about the impact?

It found a high proportion of landlords — about half — had no debt at all. Since some of the government’s changes, such as the removal of higher rate relief on mortgage interest and wear and tear allowances, affect only mortgaged landlords, many will be left unscathed. The survey also found that 85 per cent of landlords made no purchases or sales of property last year, so the stamp duty surcharge imposed on buy-to-let in April will not have touched their finances.

The authors conclude that those most likely to be affected by recent policy and tax changes are professional landlords with large, leveraged portfolios. Paul Smee, CML director-general, said there was “a certain irony” in this. “Given the government’s longstanding interest in professionalising the sector, policymakers will need to be closely attuned to the risk of unintended consequences and, indeed, own goals.”

Haven’t landlords been using corporate vehicles to avoid being hit so hard by the tax relief clampdown?

According to buy-to-let lender Kent Reliance, landlords are pouring into corporate structures, with 100,000 doing so in the first nine months of 2016 — double the figure for the whole of 2015. But the LSE study found little evidence that this was showing up yet in the overall stock of landlord mortgages, with just 3 per cent of landlords using commercial mortgages. Part of the explanation may be that moving an existing property into a limited company structure counts as a sale and purchase, and therefore attracts capital gains tax and stamp duty.