Buyers in Newry, Northern Ireland, lost it all after believing prices would keep rising – while other UK towns such as Ferryhill and Conwy are also suffering

|

But this was autumn 2007, and this was Northern Ireland. For a brief moment in time a province that was a byword for violence transformed itself into the world’s most sizzling property market. Builders who were knocking out small estates of semis initially priced at £120,000 were selling them for £200,000 on completion six months later. Investors from the Celtic Tiger south were driving north and snapping up anything they could lay their hands on. Banks were falling over themselves to lend.

To Callaghan, and thousands of others like him, it made sense to take the largest mortgage possible. He even managed to borrow some other cash and invested in a one-bed buy-to-let in Belfast.

Then the financial hurricane struck, and with peculiar ferocity in Northern Ireland. Where David bought, just outside Newry, midway between Belfast and Dublin, is perhaps the part of the UK that has suffered the biggest property boom and bust ever recorded. In March, David put the house on the market and it eventually fetched just £240,000 – resulting in a loss of £410,000.

“We’ve been wiped out,” says Callaghan, who is married with two young children. “We gathered everything together we could and sold it. We’ve sold our car, we’ve sold everything – and managed to get £17,000. So the bank has taken that, as well as the £240,000, and we now have nothing.”

He had to sell because his income has fallen heavily since 2007 and he has been struggling to pay the mortgage and childcare. “I was getting ill with it, and my wife was stressed and it was affecting our marriage. It was hanging over us like a cancer. I was having to borrow from her dad. Now we’re renting, and are much, much happier. I feel like I’ve got out of jail.” The buy-to-let in Belfast has also gone, but it wasn’t as bad an investment as the house in Newry. It only fell in value by half, not two thirds.

Claire Dempsey is another victim. She was a single woman in her mid-20s earning not much more than £20,000 a year when, in 2006, her bank offered her an interest-only loan of eight times her income. She scraped together another £23,000 from her savings and from her parents to buy a small semi for a total of £183,000. After falling pregnant and being unable to maintain the mortgage, she eventually sold it for just £65,000.

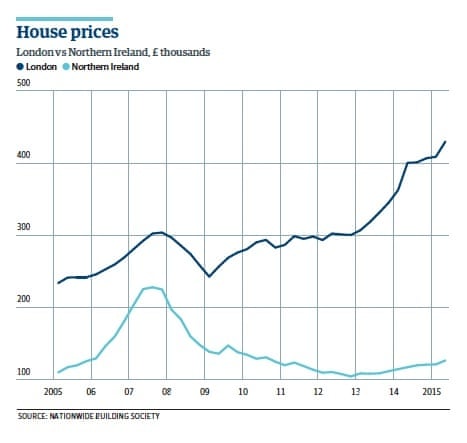

A recent tepid recovery in prices in Northern Ireland, largely in Belfast, has done little to remove the blight of negative equity. According to HML, a subsidiary of Skipton building society that handles mortgage administration for many other lenders, the number of London homes where the mortgage is higher than the value of the property is just 219 – down 99.8% in the past four years. But in Northern Ireland the figure has actually gone up since 2011, from 44,000 to more than 56,000 households with mortgages.

At Digney Boyd, one of Newry’s biggest estate agencies, director Bronagh Boyd remembers one of the fanciest properties to hit the market in 2006: a 7,000 sq ft new-build (a typical semi is 1,000 sq ft) that the developer wanted to market at £980,000. She refused to value it above £650,000. But eventually it did sell, for more than £900,000, paid for by a mortgage Boyd understands was in excess of £800,000. And now? “We sold it recently for £225,000,” she says.

The peak of the boom was in 2006. “We were doing 10 surveys a day. I was running from house to house like Anneka Rice. Now we mostly do what we call ‘shortfall sales’,” Boyd says. “We have people coming in who bought for, say, £200,000, and we say your house is worth £85,000. I’ve seen people start crying.

Land prices have fallen even further than houses. “Somebody paid £330,000 for six acres of farmland without planning permission, in the hope of getting it. We just sold it for £50,000. They were lucky, as part of it was needed for road-widening. Otherwise it was worth almost nothing.”Boyd admits she was swept up like everyone else, recently having sold her own home at half the price she originally paid. “We all went crazy. We all started to talk in millions of pounds. Now we know the value of £100.”

Yet visitors to Newry aren’t greeted by a scene of economic desolation. The city, once in the heart of “bandit country” during the Troubles, was one of the biggest beneficiaries of the peace dividend following the 1998 Good Friday agreement.

Even on a drizzly Wednesday in August its high street is bustling, largely free of the boarded-up sites, betting shops and pound stores common in the dilapidated centres of many English towns. Major retailers have invested in huge stores on the edge of town to entice cross-border shoppers from the south. Sterling’s rise over the past year has largely killed off that trade – there are virtually no Republic-registered vehicles in the car park at the Quays mall – but the shops are instead full with visitors from across the region.

A local pharmaceutical company, Norbrook Laboratories, has become the poster boy for Northern Irish corporate success, now employing 1,500 people in the area.

Another homegrown Newry success, software company First Derivatives, expects to add a further 500 jobs over the next year. On the streets, local people say that if you want a picture of economic bleakness go to Dundalk, on the other side of the border, not Newry.

So why have property prices crashed so much, and stayed low since?

Estate agents and economists are united in pointing the finger at the banks and their lending practices. While eight times income was rare, says Boyd, six or seven times wasn’t. The British banks were joined by the Irish banks, then American sub-prime lenders, in flooding buyers with easy finance. “If I were one of the banks lending at the time, I deserve to lose my shirt. They were completely reckless, not just with their shareholders’ money, but also their customers’ lives,” says David, who borrowed from one of the major UK high street banks.

David Callaghan (like Claire Dempsey, not the interviewee’s real name) prefers to remain anonymous in part through embarrassment at what happened, and in part because he is in the final stages of extracting himself from his debts.

A successful “shortfall sale” leaves the seller virtually penniless, but not bankrupt and without their credit record shredded to pieces. Several companies have now sprung up to handle negotiations between homeowners and their lenders over unmanageable mortgage debts.

In Dempsey’s case the debt shortfall was £95,000. Conor Devine, who runs brokerage Negative Equity Northern Ireland, says he was able to prove to the bank that Dempsey had no other assets.

Like the Callaghans she scraped together what she could – it added up to £3,000 – and the bank accepted that as full and final settlement of the debt. She can’t be chased for it in future, and the debt has been cancelled on her credit record. Devine says he has helped write off £12m in mortgage debts over the past six months. Crucially, the borrower has to prove they have no other assets.

Bronagh Boyd takes a similar approach. “You can’t take feathers off a frog,” she says. “All the lenders here now have shortfall teams. But you have to make sure you get the agreement before you sell.”

Many fear that the first rise in interest rates, largely because of booming conditions in London and the south-east, could finally pull the rug from many local households struggling in negative equity. Then there’s the wider problems of the province’s economy. Around 70% of it is dependent on the public sector, and austerity cuts are expected to bite hard. But Dr Conor Patterson, who runs Newry and Mourne Co-operative and Enterprise Agency, says that his biggest fear is Britain’s potential exit from the EU.

“Newry hugely benefitted from the peace agreement. If there’s a Brexit there will have to be people controls at the border, ID checks and so on. For 60% of small- and medium-sized businesses here, their primary market is the Republic. People are only beginning to realise what an exit could do to the local economy.”

Back in November 2007 the average property in County Durham was worth £113,168, writes Emma Lunn. Now it’s just £80,811, which is 29% less, according to the Land Registry

Homeowners who bought terraced houses have suffered the most. According to Home.co.uk, a terrace bought in June 2007 cost an average £71,373, but it would be worth less than half that now at just £33,875. People buying detached homes haven’t fared much better. The average price was £230,000 in June 2007, but is 40% less at £137,500 now.

Rightmove data shows how homeowners have taken a financial hit. For example, a two-bedroom terrace in Walker Terrace sold for £62,000 in August 2007, but went for just £24,500 in April 2015. Another, in Carlton Street, was sold for £45,000 in November 2007 but just £30,500 in March this year.

The town has tried to fight back, with improvements including a sports complex, a youth cafe and a station revamp.

James Bryan of online estate agent Purplebricks.com describes Ferryhill as a “gorgeous” town, but says it is plagued by a lack of amenities, with the nearest supermarket four miles away.

“House prices were the same as larger neighbouring towns, such as Darlington, Bishop Auckland and Newton Aycliffe, back in 2007-08. However, those places have developed significantly through the investment in both infrastructure and essentials for the local people, such as schools and shops,” Bryan says.

“People are buying and letting in the more built-up towns, which means that it’s a bit more difficult for the people of Ferryhill to sell or rent their property.”

According to HML mortgage servicing company, which analyses market data, about 13,230 households in Wales were in negative equity in the first quarter of this year, writes Emma Lunn. North Wales has suffered the most in the principality, with prices in Conwy county falling 4% in the past year alone. The amount of negative equity homeowners find themselves in depends on whereabouts in the county they live.

According to Rightmove, in the county town of Conwy properties cost an average of £207,171 – 7% down on £222,290 in 2008.

Things are even worse in Abergele, a small market town on the north coast of Wales. Properties sold for an average of £139,498 over the past year, 15% down on 2007 when the figure stood at £163,593. And it’s a similar story down the road in Towyn, where prices have fallen 3% over the past year and 11% since 2007.

A typical property in the coastal town is now worth £114,391, compared with £128,911 in 2007.

Adam Male, founder of the online estate agent Urban.co.uk, blames low local wages for a lack of buyers to drive the recovery in Conwy.

Despite the fall in property prices, local buyers still can’t afford to put a foot on the property ladder, particularly following the imposition of stricter mortgage requirements after the financial crisis.

“First-time buyers, an important part of the regional housing market, are renting as saving for a deposit is a distant and difficult goal. For those that do manage it, many are still priced out of the market,” he says.

“To achieve an increasing market you need all kinds of buyers who have wages to match prices, otherwise the market will correct itself. This is precisely what is lacking in Conwy county and what is, in turn, creating a lack of recovery overall.”