Why real estate investors should follow global population trends

04-19-2015

he best real estate investment in the world today? Beachfront huts in Somalia. That is according to Hans Rosling, a Swedish public health professor and data visualisation pioneer. A statistical geek is an unlikely source of property investment advice but Rosling’s rationale is convincing — and it is one that professional property developers such as Barratt and Klépierre are already putting into practice.

The explanation lies in demographics. All of the world’s forecast 3bn population growth through to 2100 will be urban, Rosling points out; a third will be in Asia, while two-thirds will be in Africa. In economic terms the developed west will grow at 1 to 2 per cent a year through until 2100, while the rest of the world will grow at 4 to 6 per cent. This amounts to a startling global shift in the pattern of trade.

“The Indian Ocean will be the Atlantic of the next generations,” predicts Rosling. As a result, the surf-beaten golden sands that stretch north from Mogadishu will make excellent holidaying territory for the Asian middle classes, several decades hence.

Somalia is a colourful example of an unlikely long-term real estate investment, but it is not the only one. As the world urbanises, it is throwing up a series of new opportunities for those willing to think a little more creatively about where to place their money.

“Particularly in Asia and the Middle East, cities are growing massively and investors are looking for alternatives to invest in,” says Mark Haefele, global chief investment officer at UBS Wealth Management. He references urban infrastructure, housing, food, water and sanitation as all being in great need of investors’ cash. As one example, he cites Asian investors who have begun to buy up Australian dairy farms.

“A lot of new cities need to be built and a lot of transport needs to be fixed and a lot of energy needs to be created,” says Rosling. He sees the greatest opportunities in people’s everyday lives. “The classic source of wealth is to fulfil the needs of ordinary families — housing, education, transport, entertainment — and that need is great in emerging markets,” he adds.

Perhaps the best example is Nigeria, which will be the world’s fastest growing country over the rest of this century, according to projections by the UN. By 2100 its population will have rocketed to nearly 1bn people, from less than 38m in 1950 and 184m today. This will make it the world’s third most populous country after India and China.

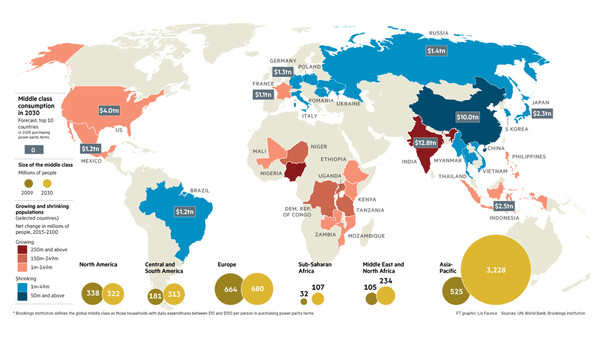

Property investment is not just about sheer numbers of people, though. Income levels are also important. The greatest growth in the middle classes is taking place in Asia. By 2030 there will be more than 3bn middle-class people in Asia, according to forecasts by the Brookings Institution, up from 525m today. India will be the world’s biggest consumer, with its middle class spending $12.8tn a year, the Brookings Institution forecasts.

Mogadishu, Somalia

Yolande Barnes, director of world research at Savills, tips Asian holiday resorts as a growth area for investors. “The wealth created in Asia has hit the cities but it hasn’t yet hit the leisure property industry, with the possible exception of Japanese ski resorts,” she says. Yet she cautions about inferring future performance from past history. “Just because Europeans enjoy lying on the beach doesn’t mean that the Chinese middle class will.”

In contrast with Asia, the number of middle-class North Americans is forecast to shrink by 16m, while those in Europe will grow by just 16m. US middle-class consumption is set to fall from $4.4tn annually in 2009 to $4tn in 2030, according to the Brookings Institution. This dramatic shift is partly driven by a general reduction in population levels. China will be the world’s biggest loser; as a result of its one-child policy, its population will shrink by 316m people over the coming eight decades — a fall equivalent in size to the whole of eastern Europe today.

Most of the world’s other shrinking populations are in developed nations. Japan is set to lose 42m people while Germany will see its population shrink by almost 26m, according to UN forecasts — a fall of almost a third. Much of this is due to declining birth rates: the number of young people is dropping in many developed economies.

Europe will see its population of 20- and 30-somethings shrink by a fifth between 2010 and 2020, a 2012 report by Deutsche Bank found. But even in nations whose population is declining, demographic analysis can highlight investment opportunities. Despite shrinking populations and static incomes, opportunities remain in the developed world.

Europe’s shrinking numbers of young people mean there will be less demand for student accommodation, fashion retail outlets, starter homes and gyms, the Deutsche Bank researchers suggest. Meanwhile the continent’s older age groups will create sustained demand for retirement homes, second homes, golf courses, nursing homes and medical facilities, they argue.

Property companies are already acting on this trend. British housebuilder Barratt Developments is refocusing its business plan away from the traditional first-time buyers — young families — and towards older people who want to downsize after their children move out.

Glen Ivy, an ‘active adult community’ in California

It is following in the footsteps of US retirement home developers, who have pioneered “active adult communities” and are now moving into multi-generational living — creating semi-independent space within a larger home to accommodate either grown-up children or grandparents.

Nation-level population trends hide a great deal of local variation, however. “Property is by definition located in one place,” says Yolande Barnes. “There is a world of difference between buying in London and buying in Hull — you might as well be buying in different countries.”

According to the Deutsche Bank researchers, younger people in mature economies are becoming more concentrated in cities, while older people stay in towns and villages.

Klépierre, Europe’s second-biggest listed property company, which specialises in shopping malls, uses demographic analysis to work out where to focus its expansion ambitions and where to sell off assets.

Just because Europeans enjoy lying on the beach doesn’t mean that the Chinese middle class will

“Demographic growth produces economic growth in a much shorter period of time — both from people moving to the place and people being born there,” says Laurent Morel, chairman of Klépierre.

As an example, he uses Madrid, now Europe’s third-largest city mostly due to a tide of immigration from Latin America and north Africa since the turn of the 21st century, although that trend has begun to reverse since the financial crisis plunged Spain and other eurozone economies into deep recessions.

Despite the ailing economy in its home market, France, Morel’s company is bullish about a handful of areas within the country, particularly eastern Paris, Toulouse and Montpellier. In the latter two, the population is increasing by about 100,000 people every five to six years, he says.

“You can afford to build a new shopping centre every time you get another 100,000 people,” adds Morel. “There are six major malls in Toulouse and we own four, and we’ll continue to build our presence in such areas.”

A shopping mall in Toulouse is a long way from a beach hut in Somalia but, as property investors around the world are finding out, the investment rationale is just the same.

Kate Allen is the FT’s property correspondent

Photographs: Petterik Wiggers/Panos; 55Places.com

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2015. You may share using our article tools.

Please don't cut articles from FT.com and redistribute by email or post to the web.