Tory policies often come from unlikely places, but when George Osborne unveiled his grand plan for a "proper garden city" at Ebbsfleet in Kent, did he realise he was backing a socialist movement for collective land reform?

"Garden city" may have become a byword for the cosy middle England ideal of privet hedges and twitching net curtains, but it began as a radical campaign for co-operative development, set out by parliamentary stenographer Ebenezer Howard in the 1890s. In reaction to the overcrowding and industrial pollution of growing Victorian cities, Howard launched his vision for a series of ideal towns, contained by rolling green belts, that would separate housing from industry and combine the best of the city and the countryside.

"Human society and the beauty of nature are meant to be enjoyed together," he wrote in Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, in 1898. "Town and Country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilization."

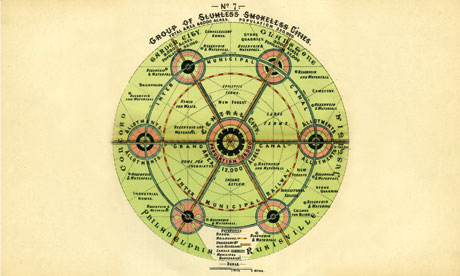

Planned on a concentric model, these garden cities would set the primary civic functions in a central park, ringed by a great glass shopping arcade, beyond which would lie halos of housing and schools, encircled by a peripheral necklace of factories and services. But fundamental to the plan was that the value would be retained in the community: every citizen was to be a shareholder, with the "unearned increment" ploughed back into civic facilities, rather than to absent landlords or speculative investors. Blue- and white-collar workers would live side by side in pastoral harmony.

Letchworth and Welwyn, the first garden cities planned in the 1910s and 1920s, stand as a testament to his thinking, although both have struggled to remain affordable, their low-density planning and fine arts and crafts houses making them hugely desirable. Welwyn's proximity to London meant it would always be more commuter dormitory town than self-sustaining city.

Affluent garden suburbs and postwar new towns would be the garden city legacy of the following decades, both of which departed from Howard's original conception of community-led planning. So how can his model be useful today?

"The principles of collective land ownership, long-term stewardship and land value capture for the benefit of the community couldn't be more relevant now," said Katy Lock of the Town and Country Planning Association, which was originally founded in 1899 as Howard's Garden City Association. "But it requires strong political leadership. Development in this country is led by short-term local politics and dominated by volume house-builders, whereas garden cities don't begin to pay back until 20 or 30 years later."

Fifteen thousand homes at Ebbsfleet may sound like Osborne's Letchworth, but there have been plans for such a development since 1996, again in 2007 and most recently 2012, yet only 150 homes have been built. "Opportunities to capture the land value for the community are much more difficult when the project is underway, with a private developer on board," said Lock. "Is it really possible to make Ebbsfleet a garden city when it's this far down the line?"